Born 14 April 1949, Dave Gibbons has already made his way into the hallowed halls of historical figures associated with comic books. It is no exaggeration to say that Gibbon’s name could appear alongside great artists and writers like Ditko, Miller, Eisner and Kubert. But while Gibbons is associated with one of the greatest (certainly the most critically and commercially successful) series of all time – his is not a career that is shrouded with his name. Whereas Quitely, Romita Jr and Kubert can occassionally dwarf a project and become the defining feature of it – Dave Gibbons has achieved something much more noteworthy – the project he works on and not his name remains the talking point of projects he is associated with. Dave Gibbons is a prolific Practitioner with a style that puts content and communication of the story first and foremost and has allowed (in a way that no other artist has been able to facilitate) a series to transcend the medium and be considered a work of awarded literature. No other artist in the medium has achieved this and that is why Gibbons is one of the most noteworthy practitioners in the list – effectively for not being as deliberately noteworthy as some of his peers. For those who know, Gibbons is a legend and one of the foremost practitioners working today.

Born 14 April 1949, Dave Gibbons has already made his way into the hallowed halls of historical figures associated with comic books. It is no exaggeration to say that Gibbon’s name could appear alongside great artists and writers like Ditko, Miller, Eisner and Kubert. But while Gibbons is associated with one of the greatest (certainly the most critically and commercially successful) series of all time – his is not a career that is shrouded with his name. Whereas Quitely, Romita Jr and Kubert can occassionally dwarf a project and become the defining feature of it – Dave Gibbons has achieved something much more noteworthy – the project he works on and not his name remains the talking point of projects he is associated with. Dave Gibbons is a prolific Practitioner with a style that puts content and communication of the story first and foremost and has allowed (in a way that no other artist has been able to facilitate) a series to transcend the medium and be considered a work of awarded literature. No other artist in the medium has achieved this and that is why Gibbons is one of the most noteworthy practitioners in the list – effectively for not being as deliberately noteworthy as some of his peers. For those who know, Gibbons is a legend and one of the foremost practitioners working today.

Gibbons broke into British comics by working on horror and action titles for British 2000AD publisher DC Thomson and IPC. With the inception of the quintessential British weekly comic publication, launched in 1977, Gibbons was in a position to contribute artwork from the very start on Prog 01. As a founding member of the title Gibbons went on to draw 24 installments of Harlem Heroes (written by Pat Mills and making up the original 2000AD ‘Thrill 5’ Line-up. It was a cross between kung fu films and the Harlem Globetrotters with the crazily violent Aeroball set in a desensitised 2050). Gibbons almost wasn’t the artist on the project, originally intended to be drawn by Carlos Trigo but for reasons unknown Gibbons appeared in the starting line up. From Prog 25, Massimo Belardinelli drew the remaining episodes of the first run and remained its regular artist for the strip’s reinvention as Inferno.

Mid-way through the comic’s first year Gibbon’s began illustrating Dan Dare, a project close to his heart as he had always been a fan of the original series, his own work inspired by Frank Hampson who had provided the visuals for DD in its earlier years. Gibbons was also inspired by Frank Bellamy, (the noteworthy) Don Lawrence and Ron Turner. whose ‘style evolved out of (his ) love for the MAD Magazine artists like Wally Wood and Will Elder.

Mid-way through the comic’s first year Gibbon’s began illustrating Dan Dare, a project close to his heart as he had always been a fan of the original series, his own work inspired by Frank Hampson who had provided the visuals for DD in its earlier years. Gibbons was also inspired by Frank Bellamy, (the noteworthy) Don Lawrence and Ron Turner. whose ‘style evolved out of (his ) love for the MAD Magazine artists like Wally Wood and Will Elder.

Also working on Ro-busters, Gibbons became one of the msot prolific of 2000AD’s earliest creators, featuring in 108 of the magazine’s first 131 Progs (issues). He returned to 2000AD in the early eighties to create Rogue Trooper with writer Gerry Finley-Day, about a cloned battle-hardened soldier and his cybernetically enhanced equipment imbued with the personalities of his fellow soldiers, providing the fans with an acclaimed early run that saw it roll well beyond his tenure under many more artists.

It was around this time he formed a working relationship with Alan Moore, working most regularly with him on his Tharg’s Future Shocks feature.

On the roll into the ’80’s, Gibbons took on the position of lead artist on Doctor Who Magazine, undoubtedly another character that’s stood the test of time more than a little well. The Doctor Who Storybook 2007 features the name ‘Gibbons’ in a list of the greatest artists of all time.

One of the British comic book talents identified by Len Wein in 1982, Gibbons was hired to draw Green Lantern Corps backup stories within the pages of Green Lantern for DC, starting with a Green Lantern story in Green Lantern 162 (March 1983) with writer Todd Klein, as well as the concurrently released ‘Creeper’ two-part back-up story in Flash 318-319. By Green Lantern 172 (January 1984) Gibbons was on the lead feature with Len Wein while still illustrating the back-up features through to issue 181. Finishing his run in issue 186 (March 1985) he briefly returned however to pencil a back up feature ‘Mogo doesn’t socialize’ with Alan Moore in Issue 188. Gibbons would later return as writer on Green Lantern Corps back up stories and his association and partnership with Moore was about to go from strength to strength, leaving him responsible for one of the foremost works of comic book fiction ever created, and by that I don’t mean ‘The Man Who has Everything,’ written in the 1985 Superman Annual by Moore and pencilled by Gibbons and collected in Moore’s greatest works for DC reprint a few years ago.

Gibbon’s clear, unrestricted and unfussy style saw him produce work for both DC’s Who Who in the DC Universe Guidebook and Marvel’s The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe Deluxe Edition. He contributed to Harrier Comic’s Brickman 1 with Kevin O’Neill, Lew Stringer and others. He provided covers for Peter David’s and Joe Orlando’s four-issue The Phantom mini-series and inked Kevin Macguire’s work on the landmark Action Comics 600 and created the cover for issue 601.

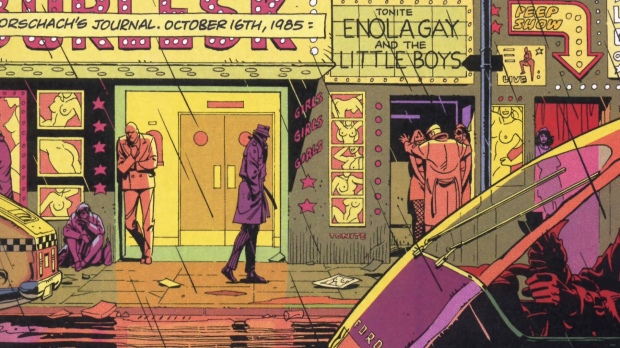

But in September 1986-October 1987 Gibbon’s joined with Alan Moore and colourist John Higgins and rendered the blood-stained smiley badge firmly in the minds of every comic reader for 25 years. Now one of the best-selling graphic novel’s of all time and the only graphic novel to feature on Time’s ‘Top 100 Novel’s List’ Gibbon’s artwork is notable for its stark utilisation of the formulaic nine-panel grid layout, removing opportunities to embellish or emphasise through scaling or composition – forcing him to rely entirely on his capacity to communicate the effect of each panel within the fixed panel shape and size itself. To have pursued this course and succeeded in the way he did, puts Gibbons in the at the table with some of the top comic book artists of all time as he put away certain stylistic tricks and still rendered a piece of graphic literature that knocked popular novels from a highly sought after list. Its dense symbolism (some suggested by Moore, some by Gibbons) is carried throughout the piece as the conflicting and complex characteristics of the central heroes is cast against a kaleidoscope of recognisable, realistic and perfectly realised environments. Watchmen in the hands of Gibbon’s is a contained beast, twice as savage with its muzzle on. The psychotic Rorschach better realised with Gibbon’s sure, naturalistic style forming a Human around a monster wherein another artist may have depicted a much more emotional and overt depiction of the same character. Gibbons and Moore’s choice to draw Dr Manhattan full frontal nude is never gratuitous and is so innate a part of the character thanks to the clear, anatomically minded style of Gibbons that the feature film 2 years ago featured the same thing – so much an ingrained visualisation of a man’s isolation from his own society that it would have altered the character immeasurably to have simply given him pants.In the Watchmen, alongside Moore, Gibbons created a timeless piece of literary history. He succeeded in depicting a disparate group of Supermen so flawlessly that Moore’s words can almost be redundant. The characters so well realised that you understand the innate characteristics they represent. Although originally intended to be the characters bought by DC from Charlton comics, the characters that were adapted from them (due to obvious concern that having bought them Moore would kill two and remove one from Human kind completely within 12 months) are familiar archetypes without ever being cliched. From the pug faced Comedian, scarred through years of hard living to Moloch, the curve eared ex-supervillain suffering from cancer, Gibbon’s gave them enough humanity to communicate all the frailties and complexities of Human beings without even once diminishing their inherent heroism.

The unmasked Rorschach – a pathetic, ungainly and slightly ugly figure when revealed from under his cowl is trapped in a cell being threatened by a criminal boss and his goons directly outside. By the end of the sequence all of the characters (save Rorschach) are dead in grotesque and memorable ways. All of this takes place in a space little larger than a toilet cubicle, in panels of 3x3x3 of equal size and largely using the same head on angle. It remains one of the most effecting and brutally challenging moments in modern comic books and its all thanks to Gibbon’s unswerving and meticulously precise style.

A giant space squid (or so it appears) destroys a city centre at the end of the Watchmen. Undoubtedly a moment that could have so easily been – and borders the absurd and tacky (and effectively the only detail of the film altered because of the difficulties in communicating it) and Gibbons communicates visually one of the most harrowing and frightening depictions of mass death to have appeared in any graphic novel with carefully rendered people piled high and strewn about the streets representing mega-death in its coldest aftermath.

Rorschach appears undisguised in early pages in crowd scenes and your eye never falls on him as he’s depicted as clearly and as obscurely as all others. But on a second glance, having been introduced to the character later on – all of what he is as Rorschach is present in the figure but entirely absent without the later revelation. Art on that level is masterful. Characterisation in remission, relying on something you will discover in order to validate it. That is Dave Gibbons the artist. Every panel retains as much information as the story needs you to know at that moment, and a thousand and one things you can acknowledge when your ready. Gibbon’s work doesn’t bait the eye – it waits for when the eye is ready for it. Few artists are more satisfying to revisit.

Rorschach appears undisguised in early pages in crowd scenes and your eye never falls on him as he’s depicted as clearly and as obscurely as all others. But on a second glance, having been introduced to the character later on – all of what he is as Rorschach is present in the figure but entirely absent without the later revelation. Art on that level is masterful. Characterisation in remission, relying on something you will discover in order to validate it. That is Dave Gibbons the artist. Every panel retains as much information as the story needs you to know at that moment, and a thousand and one things you can acknowledge when your ready. Gibbon’s work doesn’t bait the eye – it waits for when the eye is ready for it. Few artists are more satisfying to revisit.

PART 2 ON THURSDAY. INCLUDING TALES OF THE BLACK FREIGHTER, HIS INFLUENCE ON THE WATCHMEN FILM AND GREEN LANTERN : BLACKEST NIGHT