We here at Beyond the Bunker hope to list the greatest and best creatives in the history of comic books. In a continuing series (available every week on Tuesday) the most innovative, inspirational and important comic book visionaries will be appearing here. Check on the link below to see if one of your favourites has been included yet.

Mark Millar (born December 24, 1969) and is a Scottish Comic book writer. Millar was the highest selling comic-book writer working in America in the 2000s.

Millar was born in Coatbridge on Christmas Eve, 1969 in Scotland and now lives in Glasgow. In case you figured that this goliath of writing formed at the writing desk the beginning of his career was as a teenage fan. Millar was inspired to become a comic book writer following a meeting with Alan Moore (creator of V for Vendetta, Tom Strong, Watchmen and the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen) at a signing session at AKA Books and Comics when he was a teenager in the 1980s. It was not until experiencing financial problems after his parents died that he chose to leave University and become a professional writer. This tragic turn of his life and the introduction to writing as a result presents evidence of what made Millar different from many creatives. Upon suffering financial difficulty he understood that for someone determined and capable enough, writing of comic books could potentially represent a career.

His first job as a comic book writer was while he was still attending school, with Trident’s Saviour with Daniel Valley on art duties. Saviour was one of the most popular titles produced by Trident, mixing, even at that age a postmodernist blend of religion, satire and superhero action in the mix that Millar would become known for on later titles.

During the 1990s, Millar joined the creative team on 2000AD, Sonic the Comic and Crisis. In 1993, Grant Millar, Grant Morrison and John Smith presented a controversial 8-week run called the Summer Offensive in the pages of 2000AD. Morrison and Millar created a street pugilist in the chaviest sense in the pug faced Big Dave, xenophobic, ignorant, thug like man mountain who pummelled and battered his way through absurd and uniquely British threats to civilisation not the least of which a replacement boot-leg robot royal family which he battered blithely into submission to save the British isles. The first part (prog 842) saw Big Dave go up against Saddam Hussein trying to take over the world and turn everyone into ‘poofs’ with the aid od some scary aliens. Terry Waite helps him.

This mental blend of faith in your readership to get the joke, populist WAM BAM and whip crack satire and lack of fear of diving unceremoniously into the draker side of the human psyche (frankly where we are more interesting) is what set Millar apart from all the rest. Even Morrison can often loop back away from pure cynicism but Millar sees the scars in society and picks at them making him a gritty, brave and challenging writer. Which may be why he finally converted Captain America into a soldier who doesn’t kill to a one man weapon of mass destruction with a moral code firmly fixed on the defence of the weak.

Millar’s British work inevitably caught the attention of DC Comics and 1994 Millar was offered the traditional proving ground of new talent and Moore’s most sentimental character tenure some years before, Swamp Thing. Morrison aided with first four-issue run of the title to settle Millar into the title. Predictably however, while Millar’s work on Swamp Thing gained critical credit it continued to perform poorly and the series was cancelled by DC not long after Millar’s introduction. Millar continued to work on DC titles (aided occassionally by Grant Morrison – an unusual arrangement for an established writer – on titles such as JLA, The Flash and Aztek: The Ultimate Man) and working on unsuccessful pitches for the publisher. In the same period, Millar was speaking publicly and candidly about abandoning comics and had begun to mention a horror series named Sikeside for Channel 4. Sikeside was cancelled in pre-production and has recently been optioned by Crab-apple productions for a planned theatrical release.

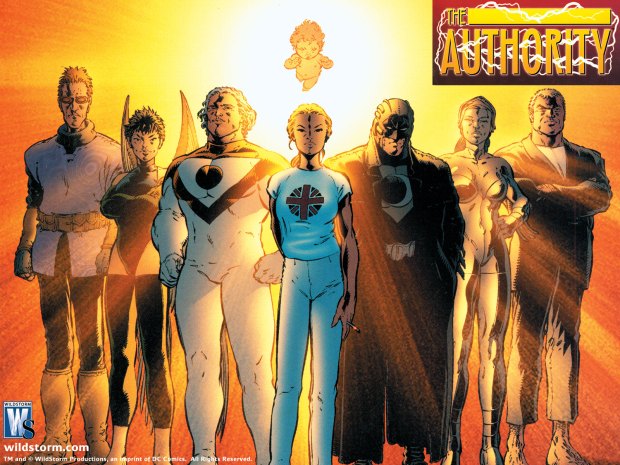

However, with the ’90s closing down behind him, unceremoniously and with little advancement the decade in which Millar will find his niche and launch Millar into the limelight began. In 2000, Millar recived his big break replacing Warren Ellis on The Authority for DC’s Wildstorm imprint. Assigned with Morrison cohort Frank Quitely to the title, The Authority launched into a more polemic style while continuing Ellis’ original big screen, broad and boundless ideals for the title. This was a team now that wouldn’t tolerate the small minded or the morally dubious powers on earth traditionally ignored by other Superheroes. Now – under Millar the Authority truly represent exactly that – unforgiving, resilient and willing to absolutely do all that is necessary to stop that which they see as wrong. The more severe and militant characters were now brought forwards as the main focus, the Midnighter even more savage and militantly cold, contentedly torturing through electrocution the former Doctor while mysteriously managing to present an entirely different image to the passing guards in a super villain prison at the end of time.

In one short scene, the newly empowered Doctor, having been handed elemental powers over creation in return for restoring the Earth to its former self overwhelms one of the female characters, the Engineer in one of the darkly subtle and emotionally affecting ways ever written in comics. The Engineer is capable of morphing technological acroutements to deal with almost any situation and presents a difficult physical threat to overwhelm for the Doctor. Until the Doctor reminds her of a medical professional at her school as a young girl who kissed her on the back of the neck while they were alone in the school nurse’s office. It is the Doctor, having travelled back, killed the nurse and planted his lips on a vulnerable and undressed little girl – leaving her with ‘a funny feeling you’d carry around for the rest of your natural life.’ This is achieved in three panels. The effect on the reader lasts significantly longer than it does on the Engineer, as a character already referred to as a genocidal maniac tips over into a more insidious and familiar evil. A hero is only as impressive as the enemy he/she overwhelms and Millar is uniquely ambiguous enough in his writing to allow his enemies to represent the worst kind of evil.

He takes this to one hell of a conclusion; because if the threat is overwhelmingly total and unremmiting what need is there for soldiers, warriors and heroes to maintain outdated and realistically outmoded perceptions of moralism in the face of global or personal threats. For thousands of years – as civilisation has prospered and gained increasingly ethical and moral positions, it has always been defended by those willing to push through the boundaries of acceptable conflict. The Second World War heroes were not made from pacifism or saving cats from trees – they were born sadly by meeting carnage and horror with strength, bravery and a willingness to push back just as hard as they were being pushed. From this idea, what would a Captain America realistically forged in the battlefields of Northern Europe and the Pacific be? A pacifist believer in all Human rights or an efficient and exacting defender of the American way. With the creation of the Ultimates – a modern and frankly more realistic interpretation of Marvel’s most iconic American hero would step to the front of the fray, at the forefront of one of the most popular series in the history of comic books. The Avengers everyone has been waiting for.

Step aside for… The Ultimate Universe.

CONTD IN PART 2 (THURSDAY)