It’s back!! Practitioners, our article featuring the people who made the comics industry is updated occasionally between issues of Moon. Practitioners Reloaded present the previous 1 – 53 (Simon Bisley – Chris Bachalo) for those who want to read more.

Born November 30th 1978 in Richmond, Kentucky, Robert Kirkman would be the only non-founding member of the third largest comic book company in the US and the creator of a black and white Zombie-fest that would be hailed as the ultimate in ‘independent’ comic books. The Walking Dead picked up on the global enthusiasm for Zombie stories and made it accessible in a way that saw it developed into a mainstream TV series.

Kirkman’s sense of identifying attention grabbing ideas is complemented by his capacity to carefully and enjoyably develop them, walking the line between enjoyment and engagement for the reader.

Kirkman’s first comic book work was the 2000 superhero parody Battle Pope, co-created with artist Tony Moore, and self published under their Funk-o-Tron label. This, perhaps, is the nature of indy publishing. A well presented, deliberately fringe creation never intended to find a place in the mainstream, that engages readers in a way the mainstream can’t and creates a viable alternative. The perfect synthesis between high (and funny) concept and professional execution (something now only too visible in British indy titles such as Lou Scannon, Stiffs and ahem… Moon).

Later, while pitching a new series, Science Dog, Kirkman and artist Cory Walker, were hired to do a Super Patriot (of Savage Dragon fame) mini series for Image Comics. Not content simply on that, Kirkman developed the 2002 Image Series Tech Jacket, which ran for six issues, with E.J. Su. In 2003, Kirkman and Walker created Invincible for Image’s new superhero line. Again, the story lines were acutely mirroring the work being produced on Marvel’s Ultimate line. Invincible, following the adolescent son of a superhero, who develops his own powers and attempts to start his own superhero career. Kirkman’s genius is an extension of Stan Lee’s some 50 years previous. It hinges on the normalisation of the super, bringing it down to the earth without an overly revealing bump.

Invincible was one of the titles that made the US comic industry a 3 company, rather than a 2 company one. In 2005, Paramount Pictures announced it had bought the rights to produce an Invincible feature film, and hired Kirkman to write the screenplay. Still nowhere to be seen, most likely the success of Walking Dead has put this particular project on the back seat for the time being.

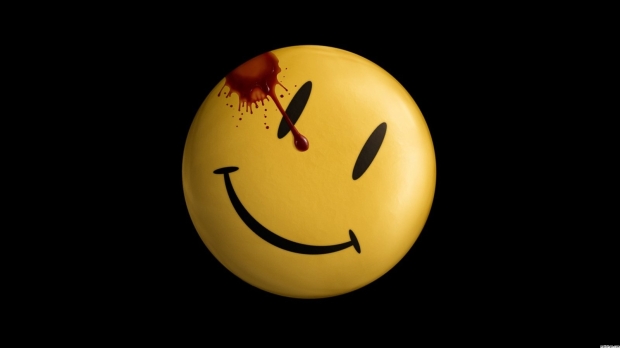

In 2003, Kirkman began his most well-known and mainstream title, The Walking Dead. It represented an unusual change in the already popular gamut of zombie material that has dominated popular culture for the last ten years. Whereas all previous appearances of the Undead had been one-offs (aside from occasional cameos in George A. Romero’s increasingly marginal series of zombie films) this was an ongoing series, with an ongoing cast and an ongoing threat. The expected result of any Zombie film is that all parties will be decimated by the final reel, the relevance of the plot being the journey those characters took in the face of an unending threat, but Kirkman’s series would cause the threat to be unending. There is no indication as to how the series might end as there is no intention for it to, only that, by Kirkman’s own volition, any character is fair game and can be killed at any time. Even the central character, County Sheriff Rick Grimes, has been given a mortality extending only as far as the reader’s interest. It’s ongoing nature has allowed ideas to be developed in ways that wouldn’t be possible otherwise. The depiction of a ‘herd’, a force of nature generated by a world populated by Zombies, in which wandering Undead intersect their ongoing paths, the rudimentary stimulus of the physical world causing them to travel in large groups, like a tide being forced through a river. Add this to the effect of a gun shot or explosion to draw the undead from a wide area and the actions of civilians in future Zombie stories will have been changed by this series.

The format also allowed the events taking place to breathe in a way that other Zombie stories couldn’t allow. Whereas convenient environments are found near-fully formed in films such as Dawn of the Dead, with access to food, water, protection, power – in Kirkman’s world, every viable haven is deficient, solutions having to be found in order to make it safe or sustainable. There is interest in this angle and Kirkman’s new format gives this subject room to be investigated. The flaw in the format however, becomes increasingly clear the longer the series runs. Kirkman has applied the rules of the Undead pretty strictly, although augmented. Those being the discovery of a world in which the Undead have taken over, the discovery of the hopelessness of the situation, the loss of society and resources, the loss of family and friends, the discovery of an enclosed haven, the failure of humanity to maintain it, the realisation that humans are the deadliest species. The difficulty with this is that the same plot has effectively been repeated several times, the inevitable breakdown of the walls around the main characters through their own actions becoming obvious and the threat of the Undead increasingly diminished as the characters and societies have to be more established in order to have survived this long. The title has slowly become a doctrine of post apocalyptic politics as the human race gains a grip on a dead world. Whether this was Kirkman’s intention is uncertain but the title remains engaging, even beyond it’s original remit and has always been written by Kirkman.

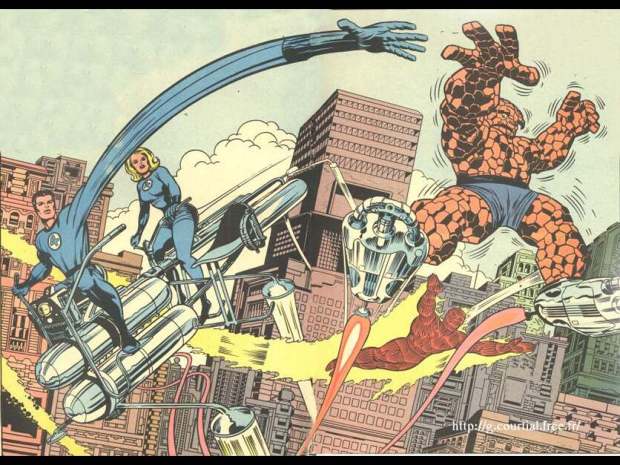

This, accompanied with a number of other projects in the same period, hired by Marvel Comics to reintroduce it’s ’90s series, Sleepwalker, sadly cancelled before being published and the contents of issue 1 included in Epic Anthology No.1 in 2004. As the Avengers became increasingly ‘Disassembled’, in Marvel’s dismantling and reboot of the central title, Kirkman was given control of Captain America (vol 4), Marvel Knight’s 2099 one-shots event, Jubilee #1–6 and Fantastic Four: Foes #1–6, a two-year run on Ultimate X-Men and the entire Marvel Team-Up vol. 3 and the Irredeemable Ant-Man miniseries.

At Image, Kirkman and artist Jason Howard created the ongoing series The Astounding Wolf-Man, launching it on May 5, 2007, as part of Free Comic Book Day. Kirkman edited the monthly series Brit, based on the character he created for the series of one-shots, illustrated by Moore and Cliff Rathburn. It ran 12 issues.

Kirkman announced in 2007 that he and artist Rob Liefeld would team on a revival of Killraven for Marvel Comics. Kirkman that year also said he and Todd McFarlane would collaborate on Haunt for Image Comics.

In late July 2008, Kirkman was made a partner at Image Comics, thereby ending his freelance association with Marvel. Nonetheless, later in 2009, he and Walker produced the five-issue miniseries The Destroyer vol. 4 for Marvel’s MAX imprint. It’s unsurprising that Kirkman wanted to continue his association with Marvel, given that he named his son Peter Parker Kirkman, after one of Marvel’s most central heroes.

In 2010, in a fanfare to the success of Walking Dead as a comic book series, AMC began it’s production of the still-ongoing Walking Dead TV Series which has become a mainstay of Sunday night viewing and has brought the original story of Rick Grimes, Lori and his son to a new and much wider audience. This has revealed the capacity for even relatively new books and concepts to find their place in wider media in an industry dominated by titles developed in some case, for more than half a century.

A surprising number of artists have failed to remain working alongside Kirkman, Cory Walker being replaced by Ryan Ottley on Invincible and Tony Moore replaced by Charlie Adlard after 6 issues of Walking Dead. While there is an innate tolerance in modern comic books on precise deadlines (mostly driven by Image and Dark Horse’s independent beginnings) this stands out with Kirkman’s almost solitary retention on the Walking Dead TV series senior team, with some extremely noteworthy walk outs (Frank Darabont the most noteworthy perhaps). These things are always subject to more politics than is publicly visible and are no doubt subject to a great many different pressures, however Kirkman is often the last man standing. This durability and sustainability perhaps the reason he has found himself in such a senior position in Image itself. However, this is open to a great deal of rumour and conjecture and is inevitable when someone such as Kirkman has risen alongside such long standing names of comic, film and TV.

Regardless of what the future holds for Robert Kirkman, he is made an indelible mark on the face of modern comics. He has moved the focus away from super hero comics, even challenging longer established characters and titles in wider fields. He has taken his place among comic book legends to run the third largest comic book company in the world, while still maintaining his own titles. Kirkman should be an inspirational figure to those in independent comics below him and an example of what careful and considered ideas, well developed can achieve.