Walter ‘Walt’ Simonson is a cheerful poster boy of independent creators within commercial comic books. An exceptional writer and artist, his love and enthusiasm for the boundless scope of possibilities available to any comic writer. His is a mind that smiles wryly at the prospect of turning a God into a frog or constantly bringing back an old idea from school to be enjoyed by many others. Simonson, more than most other artists displays an enthusiasm reminiscent of a boy. While most adults have carried the medium away from the stuff of boyhood dreams – Simonson’s work is fuelled by it creating a body of work that remains timeless and universal as childhood itself. Welcome to the House of Fun! Welcome to World of Walt Simonson!

Simonson was born in September 2, 1946. Studying at Amherst College he transferred to the Rhode Island School of Design, graduating in 1972. He found work almost immediately, at the age of 26. As his thesis, he created the Star Slammers, which was released as a promotional black and white print in 1974 at the World Science Fiction Convention in Wahington DC (also known as Discon II). A decade later the Star Slammers returned with a graphic novel for Marvel Comics, the standard of the work strong enough to go straight to mainstream publication. 10 years later, the Star Slammers returned renewed with the fledgling Bravura label as part of Image. His is the story of an imaginative artist with his own ideas, and ones that survived decades. He has won numerous awards for his work, influencing the art of Arthur Adams and Bryan Hitch.

Effectively bulleting straight out of education and directly into work, Simonson’s first professional published comic book work was Weird War Tales #10 (Jan. 1973) for DC Comics. He also did a number of illustrations for the Harry N. Abrams, Inc. edition of The Hobbit, and at least one unrelated print (a Samurai warrior) was purchased by Harvard University’s Fogg Museum and included in its annual undergraduate-use loan program. However, his breakthrough illustration job was Manhunter, a backup feature in DC’s Detective Comics written by Archie Goodwin.

Recalling in a 2000 interview, Simonson recalled that “What Manhunter did was to establish me professionally. Before Manhunter, I was one more guy doing comics; after Manhunter, people in the field knew who I was. It’d won a bunch of awards the year that it ran, and after that, I really had no trouble finding work.” Simonson went on to draw other DC series such as Metal Men and Hercules Unbound.

In 1979 Simonson and Goodwin collaborated on an adaptation of the movie Alien, published by Heavy Metal. It was on Ridley Scott’s Alien that Simonson’s long working relationship with letterer John Workman began. Workman has lettered most of Simonson’s work since. It’s a highly collaborative unity, both professionals understanding the requirements of the job; Goodman’s lettering fitting seamlessly among the bombastic and dynamic panel arrangements.

In Fall 1978, Simonson, Howard Chaykin, Val Mayerik, and Jim Starlin formed Upstart Associates, a shared studio space on West 29th Street in New York City. The membership of the studio changed over time.

In 1982, Simonson and writer Chris Claremont produced The Uncanny X-Men and The New Teen Titans Intercompany cross-over between the two most successful titles of DC and Marvel. This would undoubtedly have been a premium title given the popularity of both parties and both companies selected quite deliberately an exciting and safe pair of hands. The additional excitement that Simonson’s graphic and powerful layouts and fun style perfectly matched such a deliberately populist title, making it a valuable asset to anyone’s collection.

However it is on Marvel’s Thor and X-Factor that Simonson is best known (the latter being a collaboration with his wife Louise Simonson, who he married in 1980 and who herself would become writer on Superman titles). Walt Simonson’s brilliantly wild imagination thudded beautifully against Thor’s mythological and fundamentally otherwordly content. He took almost complete control of the title, famously changing Thor into a frog for three issues and introducing one of the most distinct characters in the Marvel Universe, the Orange, Horse Skulled, Thor matching Beta Ray Bill, an alien warrior who unexpectedly became worthy of Thor’s hammer, Mjolnir – both characters making a lasting mark on the Marvel character landscape. Starting as a writer and artist in issue #337 (Nov. 1983) and continued until #367 (May 1986), he was replaced by legend Sal Buscema as the artist on the title with #368 but Simonson continued to write the book until issue #382 (Aug. 1987) to great success.

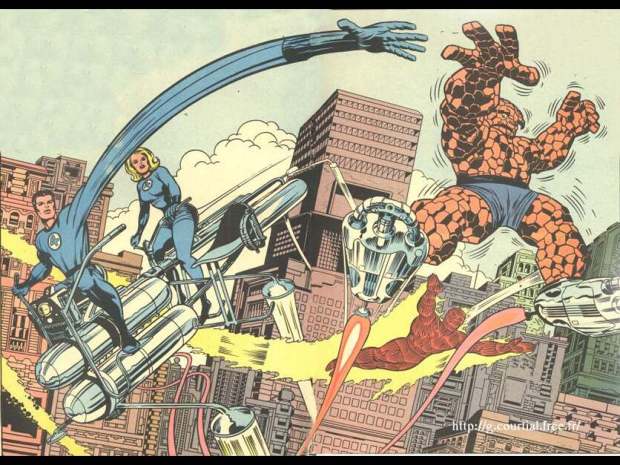

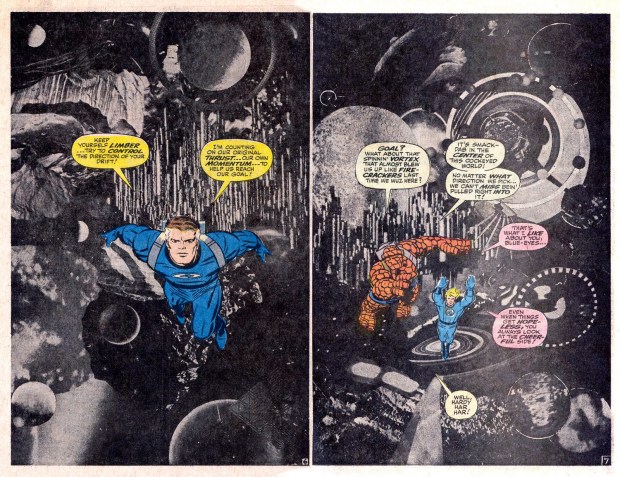

Simonson left Upstart associates in 1986. In the 1990s he became writer of the Fantastic Four with issue #334 (Dec. 1989) and three issues later started pencilling and inking as well (accidentally the exact issue he started on Thor).

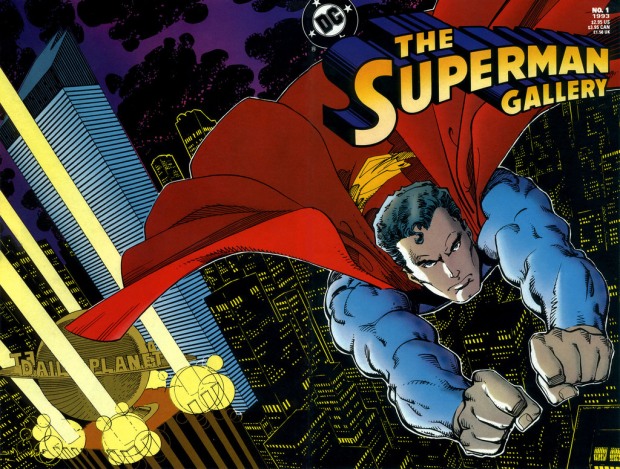

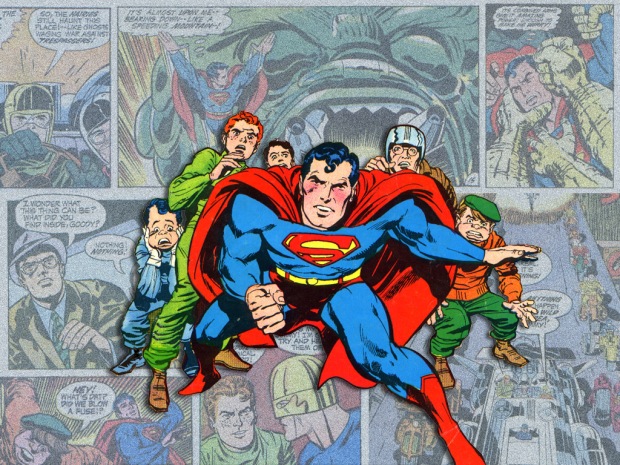

He had a popular three issue collaboration with Arthur Adams. Simonson left the Fantastic Four with issue #354 (July 1991). His other Marvel credits in the decade included co-plotting/writing the Iron Man 2020 one-shot (June 1994) and writing the Heroes Reborn version of the Avengers. His DC credits over the same period were Batman Black and White #2 (1996), Superman Special #1 (writer/artist, 1992) among others. For Dark Horse he was artist on Robocop vs Terminator #1-4. His distinctive, thick lined work matching perfectly the heavy metal nature of the storyline and central figures.

But he continued to dart seamlessly between writer and artist, never having to seek a project. His was a cheerful bounding from one distinctive project to the next across some of the greatest heroes in history.

In the 2000s Simonson has mostly worked for DC Comics. From 2000 to 2002 he wrote and illustrated Orion. After that series ended, he wrote six issues of Wonder Woman (vol. 2) drawn by Jerry Ordway. In 2002, he contributed an interview to Panel Discussions, a nonfiction book about the developing movement in sequential art and narrative literature, along with Durwin Talon, Will Eisner, Mike Mignola and Mark Schultz.

From 2003 to 2006, he drew the four issue prestige mini-series Elric: The Making of a Sorcerer, written by Elric’s creator, Michael Moorcock. This series was collected as a 192 page graphic novel in 2007 by DC. He continued to work for DC in 2006 writing Hawkgirl, with pencillers Howard Chaykin, Joe Bennett, and Renato Arlem.

His other work includes cover artwork for a Bat Lash mini-series and the ongoing series Vigilante, as well as writing a Wildstorm comic book series based on the online role-playing game World of Warcraft. The Warcraft series ran 25 issues and was co-written with his wife, Louise Simonson. As a mark of his considerable impact on Marvel’s most recognisable Norse God, in 2011, he had a cameo role in the live-action Thor film, appearing as one of the guests at a large Asgardian banquet. Simonson serves on the Disbursement Committee of the comic-book industry charity The Hero Initiative.

Simonson inked his own work with a Hunt 102 Pro-quill pen. He switched to a brush during the mid-to-late 2000s, and despite the disparity between the two tools, Bryan Hitch, an admirer of Simonson’s, stated that he could not tell the difference, calling Simonsons’s brush work “as typically good and powerful as his other work.” This is reminiscent of other master artists, such as Joe Quesada, who moved to digital penmanship from the original pen. To completely alter your tools without affecting your work is an incredibly difficult thing to achieve, particularly to a discerning eye such as Hitch’s.

Simonson is a cheerful and active character in the comic book industry. His technique is impeccable, distinct and miles ahead of his peers. His was a bombastic, thick-lined and crystal clear world. His visuals developing to meet the WAM BAM impact of 90s comics. He was a capable enough artist that at all times he appeared to be a much younger, much more modern artist. His was the legacy of the double page spread, the high impact panel and the perfect blend of effective technical skill and instinctive, intuitive and timeless visuals. More than anything Walt Simonson is fun to read and fun to look at. It’s an undervalued quality. A Simonson piece has the effect of a circus poster, triggering simple, cheerful reactions of universal ideas. His sense of humour permeates everything, his artwork bound ideas off the page.

Simonson’s distinctive signature consists of his last name, distorted to resemble a Brontosaurus. Simonson’s reason for this was explained in a 2006 interview. “My mom suggested a dinosaur since I was a big dinosaur fan.”

Says it all really.