Alan Oswald Moore looks and behaves like a Magician and declared himself one in 1994. Often considered to be the village eccentric he is (also) in fact one of the most prolific and revered comic writers in the world and the history of comics books.

Alan Oswald Moore was born 18 November 1953 in England. He is an English writer primarily known for his work in comic books, a medium where he has produced some of the most seminal pieces of comic book literature. Frequently referred to as the best comic book writer in history, Moore blends folklore, myth and legend, science fiction, mysticism, drug use, politics, and fringe culture with a healthy dose of blithe absurdism (and mild perversion) as the basis for a lot of his work. He has occassionally worked under a pseudonym such as Curt Vile, Jill De Ray and Translucia Baboon. It can be said that Moore doesn’t take himself or his work as seriously as most of those who follow it, unless it is despoiled by Hollywood, although even this he acknowledges with shrugging, friendly disinterest.

Abandoning his office job in the late 1970s for the soulless, mentally crippling waste of life that it was to a man like Moore, Moore started writing for British underground and alternative fanzines in the late 1970s, such as Anon. E. Mouse for the local paper Anon and St Pancras Panda, (a parody of Paddington Bear) for Oxford-borne Back Street Bugle. Those however had been unpaid jobs, however he gained paid work, supplying NME with his own artwork and writing Roscoe Moscow under the Pseudonym Curt Vile (a twist on composer Kurt Weill) in a weekly music magazine, Sounds, earning £35 a week. Alongside this, he and his wife Phyllis, along with their new born daughter by claiming unemployment benefit to keep themselves going. In 1979, Moore started producing a weekly strip for the Northants Post, Maxwell the Magic Cat, under the pseudonym Jill De Ray (a pun on the medieval child murderer Gilles de Rais, something he found to be a ‘sardonic joke’, giving you some insight into Moore’s inner workings.)

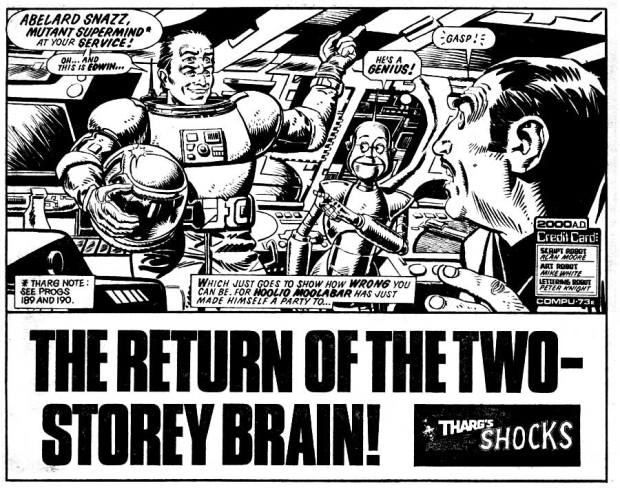

It was with 2000AD that Moore began to get into his cheerfully lunatic stride, producing Tharg’s Future Shocks prolifically from 1980 – 1984. A formulaic approach had to be used to create and complete a story in the two or three pages available which would have hampered most writers, however Moore grasped this concept and gleefully introduced world after world after world of apparently normal or absurdist characters that were then either exploded, zapped, overrun, sold, shocked, trapped or eaten by the end of the second or third page. A perfect example is a Future Shock in which a erewolf has ‘secretly’ stowed onto a starship intended to travel light years automatically to it’s destination. A dream scenario for any film, comic or TV Sci-fi writer, the possibilities are endless. However, instead of merely playing out the scenario in which the werewolf has to be stopped in the script – Moore introduces another Werewolf. Then another. Until it becomes clear that everyone on board is a werewolf and the ship is on autopilot heading into the sun. Such is the nature of Moore’s mind that he has likely forgotten he even wrote it but he simultaneously created a genre bending idea, incorporating conventions of both horror and science fiction, masterfully making the central character the bad guy and entirely unsympathetic before unceremoniously burning the assembled characters (and the plot line) in a sun in a way that makes you chuckle to yourself. Moore simply never concerned himself with the idea that he would run out of ideas. In his defence he never has. A ferocious reader, he absorbs subject matter as quickly as he generates it, like some intellectual symbiont that looks like Santa on crack, gnawing on the shape of the universe and regurgitating bits of it, now fused and unrecognisable.

So impressed were 2000AD with Moore’s work they offered him his own series, based very, very loosely on E.T. A series to be known as Skizz, illustrated by Jim Baikie. Ever critical of his own work, Moore later opined that in his own opinion ‘ this work owes far too much to Alan Bleasdale.’

Add to that the anarchic D.R. and Quinch, illustrated by Alan Davies, which Moore described as ‘continuing the tradition of Dennis the Menace, but giving a thermonuclear capacity,’ followed two anarchic aliens, loosely based on National Lampoon’s O.C. and Stiggs. Ever the innovator, Moore (with artist Ian Gibson) introduced a deliberately feminist title, based around a female character (a first for 2000AD at that time), The Ballad of Halo Jones. Set in the 50th century, it went out of print before all the progs were completed by Moore.

Unusually, and unbeknownst to may, Moore took on Captain Britain for Marvel UK, taking over from Dave Thorpe but retaining the original artist Alan Davis, who Moore described as ‘an artist whose love for the medium and whose sheer exhultation upon finding himself gainfully employed within it shine from every line, every new costume design, each nuance of expression.’ However he described his time on Captain Britain as ‘ halfway through a storyline that he’s neither inaugurated nor completely understood.’

But it was under Dez Skinn, former editor of both IPC (publishers of 2000AD and Marvel UK), over at Warrior that Moore finally kicked into high gear and started moving towards his massive potential. Moore was working on Marvel Man (later named Miracleman), drawn by Garry Leach and Alan Davies. Moore described it as ‘(taking a) kitsch children’s character and (placing) him within the real world of 1982’ and The Bojeffries Saga, a comedy abouta working class family of Vampires and Werewolves, drawn by Steve Parkhouse. But it was another title, which showcased in 1982 alongside Marvel man in the first edition of Warrior in March 1982.

This was V for Vendetta, a dystopian tale set in London 1997, in an England now run by a fascist regime. The only resistance to this is a masked Guy Fawkes figure who bombs empty iconic government buildings and attempts to foster anarchy in the name of freedom. Moore was influenced by the pessimism that was rife over the conservative government of the time, only creating a future where sexual and ethnic minorities were incarcerated and eliminated. V for Vendetta struck a chord at the time but has lost little popularity through the years – regarded as a seminal work, V for Vendetta is a clear marker in the career of potentially the foremost comics writer of our time. Illustrated by David Lloyd, it’s a lodestone of pent up left wing aggression towards an increasingly reactionary conservative government and like all great literature is loaded with parallel themes inherent in the society of the time. Whether it’s the Crime and Punishment of comic works is another matter, but it remains a poignant and thought provoking piece that will most likely retain it’s popularity well into the future – and certainly for as long as Moore remains a popular writer.

Moore was a phenomenon, his scripts generating the most consistently well rated pieces in 2000AD he grew unhappy with the lack of creators rights in British comics. This would become a consistent problem with future publishers as well, as Moore refused to accept the situation. Talking to Fanzine, Arkensword in 1985 he noted that he had stopped working for all publisher except IPC ‘purely for the reason that IPC so far have avoided lying to me, cheating me or generally treating me like shit.’

He did, however, join other creators in decrying the wholesale relinquishing of all rights, and in 1986 stopped writing for 2000 AD, leaving mooted future volumes of the Halo Jones story unstarted. Moore’s outspoken opinions and principles, particularly on the subject of creator’s rights and ownership, would see him burn bridges with a number of other publishers over the course of his career – but this has rarely done anything but feed Moore’s reputation as an anarchic presence in an industry that, in appearance anyway, runs creatively on anarchy.

During this same period – using the pseudonym Translucia Baboon – became involved in the music scene, founding his own band, The Sinister Ducks, employing a young Kevin O’ Neill to complete the sleeve art. In 1984, Moore and David J released a 12-inch single with a recording of ‘Vicious Cabaret’ a song featured in the soundtrack of the movie adaptation of V for Vendetta, released on the Glass Records label. Moore also wrote ‘Leopard Man at C&A’, which was later set to music by Mick Collins to appear on the Album We Have You Surrounded by Collins’ group the Dirtbombs.

But, musically speaking it wasn’t Leapordman that would occupy his future but a Swap Thing. Alan Oswald Moore was beginning to be noticed on the far side of the Atlantic by Len Wein, DC Comics Editor.